With a nostalgic nod to dressing, we rediscover the sentimental value that precious brooches may hold

My grandmother's jewellery box was lined in velvet and hinged in gold. It sat atop her dresser, catching the light in the afternoon, and when you lifted the lid, a ballerina began to turn to Greensleeves. I raided it constantly. I was no older than five, elbows on the duchess, twisting clasps and prising open brooch pins I had no business touching. It was the brooches I loved the most—enamelled violets, little gold bows, paste-stoned daisies, all inexplicably heavy for their size. Besides her strings of beads and ‘pearls’, they were the only pieces I ever remember my grandmother wearing. Always one fixed to a cardigan or sweater, sometimes two if she was feeling fancy. The rest of the box was off-limits. But the brooches, those felt like fair game.

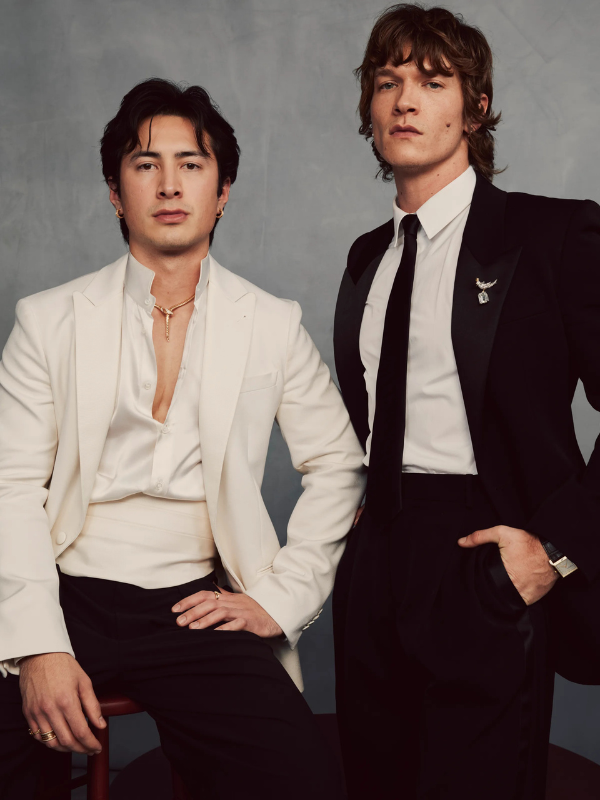

It makes sense that they’re back. In an age of transient trends and screen-based dressing, brooches offer something tactile and slow. They’re personal, they're weighted. They sit close to the heart. This season, they’ve resurfaced everywhere—on the runways at Prada, Miu Miu, Gucci, Loewe, and on red carpets in increasingly maximalist clusters (see: Rihanna in Schiaparelli; Florence Pugh in sheer Valentino and a pearl-pin mashup; Connor Storrie in what the internet dubbed 'a slutty little brooch'). It’s a revival, but it’s also a return to form. Brooches have always held meaning. Roman fibulae fastened togas and marked status, while Victorian brooches were worn in mourning or love. The Queen wore them like symbols—fern-leaf shapes for New Zealand visits, aquamarine sets gifted on her eighteenth birthday. A brooch wasn’t just decoration; it told you who someone was.

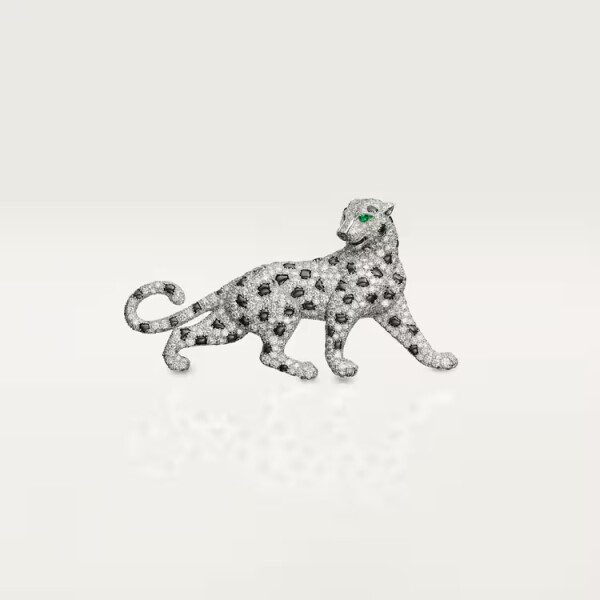

Cartier Panthère de Cartier brooch

Cartier’s Panthère, for instance, is far more than a motif. It was a mark of power—first designed as a brooch for Jeanne Toussaint in 1948, the feline became shorthand for the maison’s bold femininity. Tiffany & Co.’s enamelled orchids, made by Paulding Farnham in the 1890s, were equally evocative: lush, lifelike, and distinctly American. More recently, under Ruba Abu-Nimah, Tiffany & Co. was styling its brooches on denim and trenches—less gala, more grounded. At Van Cleef & Arpels, transformability is key: the ballerina clips of the 1940s (inspired by Balanchine himself) or the iconic Zip necklace, which doubles as a brooch, speak to a kind of romantic ingenuity. It’s luxury, yes, but not the kind that sits on a shelf. These pieces were meant to move, to be worn, re-worn, inherited. My grandmother’s weren’t Bvlgari or Cartier—but they might as well have been, given how much I adored them.

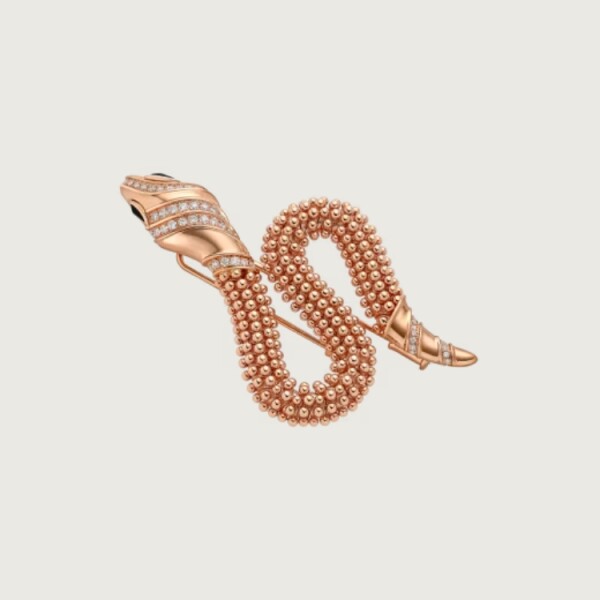

Part of the brooch’s appeal is that it straddles the sentimental and the declarative. It says something. Whether it's pinned on a collarbone or tucked into a beret, it punctuates a look with intent. It’s not performative in the same way as an emblazoned logo, but it does speak: to history, to whim, to taste. Bvlgari’s La Dolce Vita-era brooches, with their oversized cabochon stones and sun-drenched palette, speak to unapologetic sensuality. Jean Schlumberger’s Tiffany & Co. sea creatures—the bird-on-a-rock, the starfish—veer toward play. Art Deco brooches from the 1920s–30s, especially those by Cartier, were graphic, linear, and bold. They were wearable architecture.

Bvlgari Serpenti brooch

Now, they’re also collectable. Resale sites like Vestiare and The RealReal have seen a spike in searches for vintage brooches—not just because they’re beautiful, but because (if you take care of the pin) they’re built to last. Brooches aren’t dictated by season or neckline. They can be worn on hats, bags, sneakers, shoulders. They’re genderless, memory-soaked, and increasingly sustainable. There’s something subversive about wearing one now, precisely because it feels so not of the moment—even though red carpets would suggest otherwise.

I don’t know where most of my grandmother’s brooches ended up. I like to think they’re somewhere being worn by one of my many aunties or cousins—a little off-centre, clasped through a knit, or anchored to a lapel. Maybe one day I’ll find one in a secondhand store down south, and I’ll know it by feel.